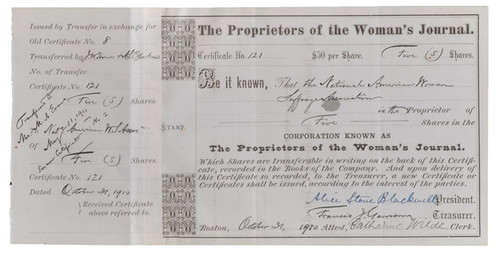

ALICE STONE BLACKWELL (1857-1950). Blackwell was a reformer and a women's suffrage leader. Her parents, Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell, were rivals of Susan B. Anthony, and each formed their own associations, only to be merged into the National-American Woman's Suffrage Association in 1892. 1910, Boston. A stock certificate signed issued to the National American Woman's Suffrage Association and signed “Alice Stone Blackwell” as president of the Proprietors of the Woman’s Journal. As noted on the stock stub, these shares were originally transferred by Julia Ward Howe to Alice Stone Blackwell The partly printed black and white certificate is for five shares bought by the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Light ink splotch at center. Extremely fine.

Founded in 1870 by Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Blackwell, The Woman's Journal, which espoused the moderated philosophy of the American Association's women's movement, was the most influential voice in the struggle to grant women their right to vote. While another leading women's journal of the times, The Revolution, which rejected the National Association's more aggressive and radical views on women's rights, ceased publication in 1872 due to lack of funds, The Woman's Journal remained the foremost advocate of the women's rights movement.

Under the devoted leadership of Lucy Stone and Henry Blackwell, as well as Julia Ward Howe, Mary A. Livermore, Thomas W. Higginson, and Henry Ward Beecher, the American Association was consistently conservative and believed that patience, hard work, and education - not aggressive confrontation, which the National Association promoted - would result in their achieving their goals. As stated in the masthead of The Woman's Journal: "The Woman's Journal is devoted to the interests of WOMAN, to her educational, industrial, legal and political equality, and especially to her RIGHT OF SUFFRAGE." The journal was published weekly in Boston, Chicago and St. Louis.

An excerpt from Harper's Weekly in 1872 assessed the Journal as "a fair and attractive paper in appearance; while the variety and spirit of its articles, and the dignity, self-respect, good humor and earnestness of its tone will show how profoundly mistaken are those who suppose that folly and extravagance are necessarily characteristic of the discussion of the question" (of women's rights).

Lucy Stone was far ahead of her time in her struggle for women's rights. Although her father, a well-to-do farmer and tanner who believed that men were divinely ordained to rule over women, refused for many years to allow her to have a college education. Lucy was determined to educate herself learning Greek and Hebrew in order to better interpret the Bible. An advocate of the Anti-Slavery cause, she lectured regularly on the issue. Lucy met Henry Blackwell , also an activist in the Anti-Slavery movement and a supporter of women's suffrage, in 1853. When they married, she kept her maiden name because she felt that "a woman's abandonment of her name upon taking a husband was symbolic of her loss of individuality." Following their marriage, the couple campaigned in Kansas on behalf of state amendments extending suffrage to women and Negro men. In 1870 they assumed the editorship of The Woman's Journal, which they continued for the rest of their lives. Their daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell, became editor upon her father's death in 1909.

The Journal, to which the family invested their total energies throughout their lives, has remained a most authoritative historical record of women's rights; its historical, political and social significance cannot be overstated.